Monday, April 13, 2009

Sunday, April 12, 2009

Georges Bataille The Dead Man pt. 2

About Story of the Eye Roland Barthes says "the erotic theme...is never directly phallic." And Michel Leiris writes concerning the novel's erotic activity; "innumerable possible permutations in a universe so little hierarchized that all is interchangeable there." Bataille replaces the strictures of gender, sexuality and hierarchy, with the orgy of metaphoric chains and their inexorable combinations; eye/egg/testicle.

Georges Bataille The Dead Man pt. 1

"All it takes is to imagine suddenly the charming little girl whose soul would be Dali's abominable mirror..." If I had to imagine Bataille's

"All it takes is to imagine suddenly the charming little girl whose soul would be Dali's abominable mirror..." If I had to imagine Bataille's"charming little girl" she would be the blonde, demonic child that appears at the end of Fellini's short film Toby Dammit. An incarnation of Satan holding a large red ball which is really Toby's head lost in a wager. She would bear the names: Simone, Marcelle, Lazare, Dirty, Eponine, and of course Marie.

How does one explain Bataille's body of work, which like all bodies, physical and metaphorical, is assumed to be unified but contains on the one hand the jerking off of an encephalitic dwarf and on the other a critique of the Marshall Plan.

Perhaps it is necessary to reconstruct the image of the "body" of the work. In Bataille’s case we could begin by severing the Cartesian head that thinks with a "clear and assured consciousness of that which is useful in life." The body of the work no longer a seamless whole, composed of a series of discourses revealing a full positivity but a body like the image of the Acephale; headless, sacred heart in its right hand, dagger in its left, self-mutilating, a labyrinth of entrails, the skull of genitals. The bowels are a labyrinth where food finds its soul to be shit. The night is a labyrinth where Marie...

Saturday, April 11, 2009

The Whiteness of the Teletubbies' Sun

This short clip from a popular children’s television show entitled The Teletubbies illustrates British film scholar Richard Dyer's thinking on “whiteness”. The opening sequence with this particular baby in the sun begins and ends every episode of the program. Keep in mind that the producers of The Teletubbies made every effort to maintain diversity in all other areas of this television show but not in this opening sequence. For example, the Teletubbies themselves are "racially" diverse, showing different shades in their skin color and body color. Also the Teletubbies have little television screens that show short movies about real children; these movies once again portray racial and ethnic diversity. Richard Dyer’s book White (1997) explains this blind spot in the thinking of the producers of The Teletubbies; the "white" race of the baby overlaps with all sorts of meanings connected to the color white. In other words, this blind spot in the show - why it has to be that baby and no other - plays into ideologies and mythologies of “whiteness” as a race and its connection to the symbolism of the color white (in this case, whiteness as light).

Friday, April 10, 2009

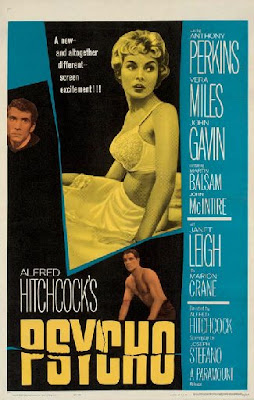

Psycho

Norman Bates is not external to American life but is part of the regular patterns and behaviors that typify it. With Psycho the events of horror and the existence of monsters is now a product of the American way of life. Compare Norman to the monsters of the classic horror films who were different from us, not only in their “abnormality”, but also in their foreignness. We are frightened by the classic monsters not only for their perversity and malformation, but also for their difference. With their foreign accents and connections to faraway lands, the classic horror film monsters are really outsiders bent on disrupting our way of life. (We need only think of Dracula). The narratives of these classic horror films frequently end with the vanquishing of the exotic monster and the ideologically strengthening of the borders of normality within our nation and our psyches. With Norman Bates the monstrous comes from the institution that is closest to home and at the heart of American life; the family.

Norman Bates is not external to American life but is part of the regular patterns and behaviors that typify it. With Psycho the events of horror and the existence of monsters is now a product of the American way of life. Compare Norman to the monsters of the classic horror films who were different from us, not only in their “abnormality”, but also in their foreignness. We are frightened by the classic monsters not only for their perversity and malformation, but also for their difference. With their foreign accents and connections to faraway lands, the classic horror film monsters are really outsiders bent on disrupting our way of life. (We need only think of Dracula). The narratives of these classic horror films frequently end with the vanquishing of the exotic monster and the ideologically strengthening of the borders of normality within our nation and our psyches. With Norman Bates the monstrous comes from the institution that is closest to home and at the heart of American life; the family.